On Invention and Discovery

For millennia, one of the most fundamental questions in the philosophy of mathematics has plagued some of the greatest minds in history. Is mathematics something which has been invented by human beings or is it something inherent to the universe which we discover and explore? If it is something which is invented, how is it possible that surprising and often counterintuitive results in mathematics are often eerily applicable to the world around us? If it is discovered, then how is it even possible for non-physical mathematical entities to exist in order to be discovered– and how do we even have access to them that they might be discovered?

The simple fact of the matter is that mathematics is, and always has been, both. Humanity has invented rules for describing the world around us which we call “mathematics.” Then, by following the implications of those rules through to their logical conclusions, we make discoveries which may not have been originally obvious.

Now, before I explicitly discuss why I believe this to be the case for mathematics, allow me to use an analogy which will illustrate exactly what I mean. Consider the example of the game of Chess. There is no denying that Chess is a human invention. It is a game played on a checkered board with little carved figurines. Each of those little figures is given a name and has been assigned ways in which it can and cannot move. The game has rules which were invented and changed over centuries of play, but which have become so commonplace throughout the world that it is almost universally recognized, regardless of one’s cultural, linguistic, or academic origin. Chess is clearly a human invention.

However, there are things about Chess which are certainly discovered. The overwhelmingly vast majority of recorded games for the past 100 years have opened with either 1. e4 or else 1. d4, moving either the pawn in front of the white king or else the one in front of the white queen, respectively, two squares directly forward. There is nothing explicit in the rules which would make these moves preferred over moving any of the other pawns or the knights. And yet, of the nearly 4 million games in the Chess.com database as of the writing of this article, more than 3.29 million (82.25%) opened with one of those two moves. This is because centuries of playing the game, exploring its possibilities, and testing different ideas have shown that these two moves offer far better chances for creating winning positions later in the game than do any others. The rules of Chess were invented, to be certain; but the best moves to play in order to win the game are discovered.

This is directly analogous to mathematics. Tens of thousands of years ago, when humanity first came up with ideas about how they could communicate the concept of quantities between one another, people came up with rules by which these things could be discussed. The rules were likely quite simple, at first, but as people began to describe more complex ideas, they added to and altered the rules. The earliest rules which were invented to describe quantities were likely the concepts of “smaller than” and “equal to.” Once we have invented those simple rules, we can discover the concept of counting within them.

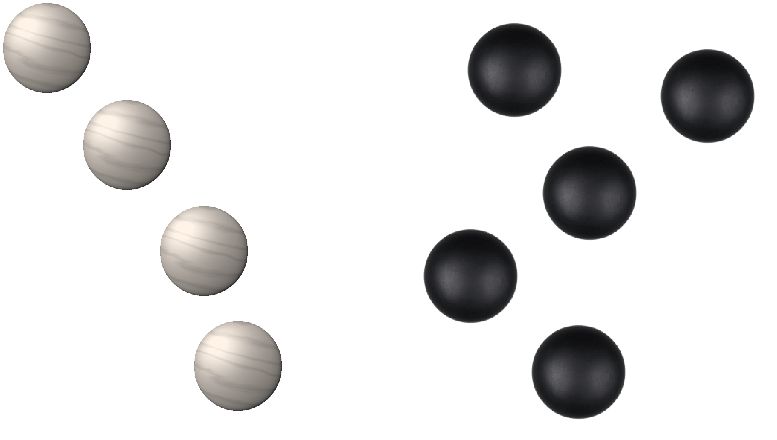

What do I mean by that? Consider the figure below in which we have a group of white stones and a group of black stones. Now, without using any numbers, what does it mean to say that either of these groups is “smaller than” the other? Let’s invent a very simple rule for the concept of “smaller than” which will always consistently compare these groups of objects and yield the same results every time.

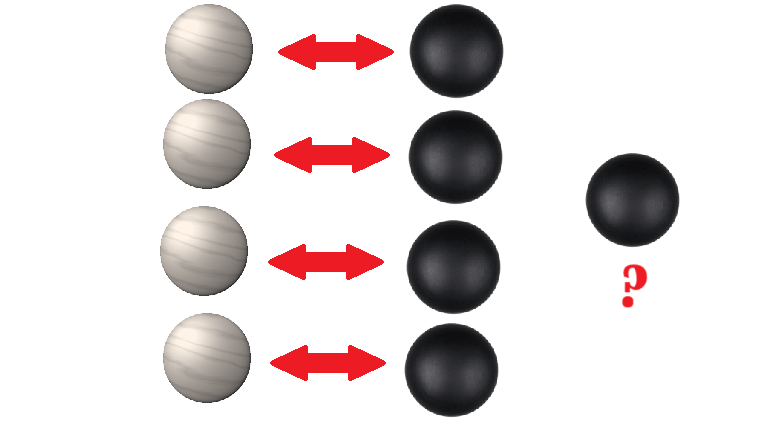

Now, let’s pair off stones from each group, matching a white stone with a black stone until either of the groups has no stones left to pair, as in the next figure. When we do, we find that the group of black stones has a remaining item which we were unable to pair with a white stone. The fact that the group has leftover, unpaired items when we do this defines our concept of “smaller than.” The group of white stones is “smaller than” the group of black stones because it does not contain enough items to pair each exactly with the other group.

Now that we have a definition for “smaller than,” we can conceivably look at any group of objects and tell whether it is “smaller than” another group of objects or not. So, for example, we can see that the white stone group is “smaller than” the black stone group; and that the black stone group is not “smaller than” the white stone group. However, this brings to mind an interesting idea– what if we have a case in which the white stone group is not “smaller than” the black stone group, but neither is the black stone group “smaller than” the white stone group. In that situation, we would say that the group of white stones is “equal to” the group of black stones.

Having invented these two simple rules, we can discover a new concept which we will call “ordering.” From here on, I will use the symbol “<” as shorthand for the phrase “smaller than.” Let’s say we have some groups of objects which we will call A, B, and C. Now, let’s say that using our rule from above we discover that A<B and that B<C. Well, if A did not have enough items to pair completely with B, and B did not have enough items to pair completely with C, it is a simple deduction to see that A cannot possibly have enough items to pair completely with C. Thus, without even needing to perform our comparison algorithm directly between A and C, we have discovered that A<C. Similarly, for any given group X such that C<X, it must follow that A<X and also that B<X. Thus, we find that A<B<C<X. This is what we mean by “ordering.” We have discovered that our rule for “smaller than” has further implications inherent in it. We didn’t have to invent this as a new rule. Rather, it is a necessary consequence of the rules which we already had in place.

This idea of ordering can then be used to discover counting. Counting can be used to discover addition and subtraction. Addition and subtraction allow us to discover multiplication and division. Our very simple rules allowed us to discover much more powerful tools.

Eventually, our simple rules might prove inadequate to the task we’re trying to accomplish. In such cases, we might invent a new rule. Then after we add that rule, we have a whole new universe of discoveries to make from the implications of that rule. This has happened time and time again in the history of mathematics. When whole numbers proved inadequate for our goals, humanity invented the concept of rational numbers. When the rational numbers were not enough, we invented the idea of irrational numbers. We continued adding more and more such rules as mathematics developed: the number zero, negative numbers, complex numbers, infinitesimals, limits, Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, et cetera, et cetera.

And each time humanity added new rules, new mathematical discoveries loomed just behind them. Mathematicians have spent millennia exploring the maddeningly complex implications of relatively simple concepts. We’ve invented entirely new methods for doing mathematics and then explored those implications, as well. Entire fields of academia are dedicated to very specific avenues of these sorts of discoveries. For those who have spent their lives pursuing mathematical understanding, this exploration and discovery feels akin to the journeys of men like Leif Erikson and Marco Polo and Zheng He and Ferdinand Magellan.

Humanity invented mathematics. However, the implications of that invention have provided us with almost limitless room for discovery within that framework.